Laurent Mfugale of UWAMIMA tells about the challenges they have faced, such as transport permit from the government, lack of weighing scales and government regulation on timber drying fee. Today, several of these challenges are overcome, and the timber marketing center is progressing. Photo: Jenny Öhman / FFD.

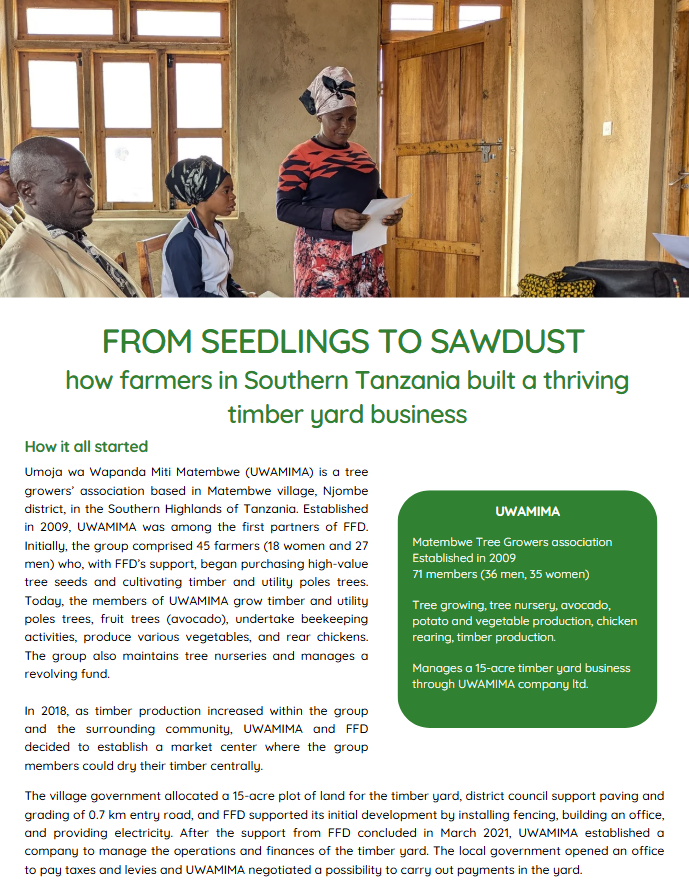

How it all started

Local youth at work loading the timber trucks. Photo: Tuuli-Maria Mäki / FFD.

Umoja wa Wapanda Miti Matembwe (UWAMIMA) is a tree growers’ association based in Matembwe village, Njombe district, in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Established in 2009, UWAMIMA was among the first partners of FFD. Initially, the group comprised 45 farmers (18 women and 27 men) who, with FFD’s support, began purchasing high-value tree seeds and cultivating timber and utility poles trees. Today, the members of UWAMIMA grow timber and utility poles trees, fruit trees (avocado), undertake beekeeping activities, produce various vegetables, and rear chickens. The group also maintains tree nurseries and manages a revolving fund.

In 2018, as timber production increased within the group and the surrounding community, UWAMIMA and FFD decided to establish a market center where the group members could dry their timber centrally.

The village government allocated a 15-acre plot of land for the timber yard, district council support paving and grading of 0.7 km entry road, and FFD supported its initial development by installing fencing, building an office, and providing electricity. After the support from FFD concluded in March 2021, UWAMIMA established a company to manage the operations and finances of the timber yard. The local government opened an office to pay taxes and levies and UWAMIMA negotiated a possibility to carry out payments in the yard.

The UWAMIMA timber marketing center in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania was established in 2018. Photo: Jenny Öhman / FFD.

A unique farmer-led business

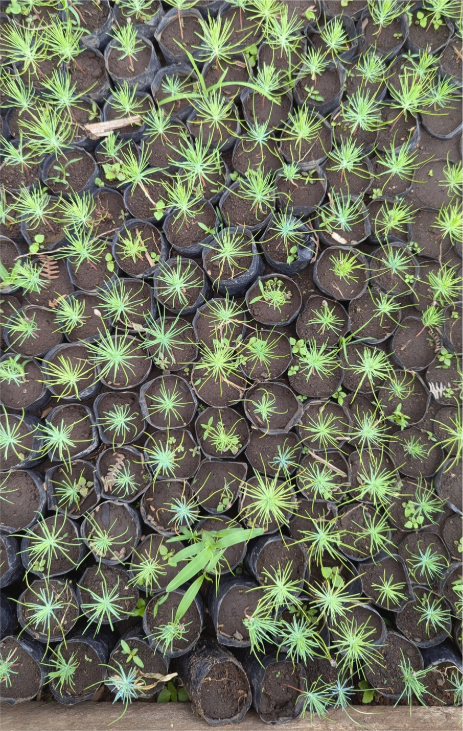

Pine tree seedlings in UWAMIMA’s tree nursery. Photo: Tuuli-Maria Mäki / FFD.

Tanzania Tree Growers’ Associations’ Union (TTGAU) has also been instrumental in supporting the timber yard’s business development and governance. TTGAU was founded in 2017 and has already gained a strong position in the forestry sector in the Southern Highlands area. They have helped UWAMIMA strengthen its management structure and engage in dialogue with local, regional, and national authorities. With the union’s help, UWAMIMA managed to negotiate the abolition of an extra drying fee and reduce the levies and taxes that the municipality was requesting from timber trucks, which threatened the whole timber trade. TTGAU was one of FFD's partners in the FO4ACP programme during 2023-24. While the main focus was to support different tree growers' associations to prepare for FSC certification, a small support was also given to the UWAMIMA timber yard to fix the feeder road which had been damaged by heavy rains.

Visiting UWAMIMA timber marketing center in 2023 with FFD, TTGAU and 30 stakeholders from FAO’s Forest and Farm Facility, government representatives from 6 regions, Tree Growers Associations and local NGOs. Photo: Jenny Öhman / FFD.

Being the only farmer-managed facility of its kind, UWAMIMA’s timber yard is unique and striving to serve as a model for other farmers. Members can dry their timber at the yard free of charge, while other plots are rented out for business purposes. Over the past three years, the group has successfully managed the timber yard, achieving significant progress. They operate a tree nursery, grow high-value timber trees, and empower both women and men to engage in more profitable ventures. The market center has created a steady income stream while also generating tax revenue for the local government. The timber yard has helped farmers to enhance the timber value chain, enabling them to secure fair prices for their timber. Unlike in the past, when middlemen dictated terms, members can now negotiate directly with buyers and achieve better margins. Compared to growing crops like avocado, timber cultivation has proven to be more cost-effective.

Making a long-lasting local impact

The timber yard’s impact on UWAMIMA members is profound. With easier market access and reserved plots for storing timber, farmers can choose to sell immediately or wait for better prices. The group has implemented a market information system to monitor timber prices, supply, and demand, providing members with more predictable pricing before deciding to sell or process their woodlots. Improved processes ensure no timber is processed without a prior woodlot evaluation, securing income for the farmers. This success has doubled UWAMIMA’s membership since the beginning and created valuable employment opportunities for local youth; approximately 85 young men are currently employed sorting and loading timber. This temporary employment at the timber yard is one of the few opportunities for youth to make a living in the village.

Women’s participation in the timber business has also increased significantly. Women play a pivotal role in Tanzania’s forestry sector, serving as change agents at various levels. They contribute labor as family members, own forests, and manage businesses. UWAMIMA has showcased that women can not only provide labor in the forest sector but can as well own forests and engage in different levels of the value chain. They establish and manage nurseries, woodlots and market forest products. Now the women have gained a much stronger presence in the village economy and governance.

Women’s participation in the timber business has increased significantly in the last years. Photo: Tuuli-Maria Mäki / FFD.

Business improvements are still ongoing, with plans to acquire a new sawmill and to mobilize the group members to diversify their economic streams and to plant and protect more trees. Alongside these advancements, a noticeable transformation has occurred in members’ attitudes and confidence. They are more self-assured, innovative, and equipped to drive their business forward. Secured income also allow members to focus on broader goals, such as cultivating indigenous tree species to enhance biodiversity.

FFD and TTGAU visiting the timber yard in Matembwe in October 2024. Photo: Tuuli-Maria Mäki / FFD.